| |

Pressure Areas, Continued

Isobars,

continued

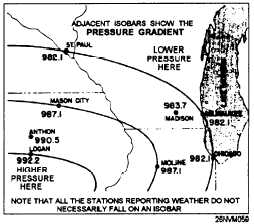

Usually, isobars are drawn for equal intervals of pressure (every 4

millibar for example), and frequently, isobars do not pass through

reporting stations. Isobars never join or cross. Some may run off the

chart, but others may close, forming irregular ovals that define the areas

of highest and lowest pressure (fig. 10-6). Air (wind) flows from high-

pressure areas to low-pressure areas. The strength of the wind depends

upon two factors: the amount of difference in pressure and the distance

of the high-pressure area (high) from the low-pressure area (low). These

two factors combined are called pressure gradient. The greater the

gradient, the stronger the wind. Thus, isobars can give a rough

indication of the amount of wind. The closer an isobar is to another, the

greater the amount of wind in that area. In figure 10-7, the isobars

represent pressures of 992.2 mb, 987.1 mb, and 982.1 mb.

Figure 10-7. Isobaric patterns.

The spacing and shape of isobars are seen in figure 10-6, which also

shows how complete isobars are formed. Isobars are always smoothed-

out curves, usually making irregular ovals around the high- or

low-pressure center.

Refer to figure 10-7 and you can see that only part of each isobar (the

upper right portion of the oval) appears in the diagram. In this pressure

system, that area of greatest pressure is at the system’s center. This

high-pressure area is also called a high or an anticyclone. If the

pressure is 992.2 mb at Chicago, 987.1 mb at Moline, and 982.1 mb at

Logan, the area of lowest pressure is in the vicinity of Logan. This area

would be a low, or a cyclone.

10-14

|